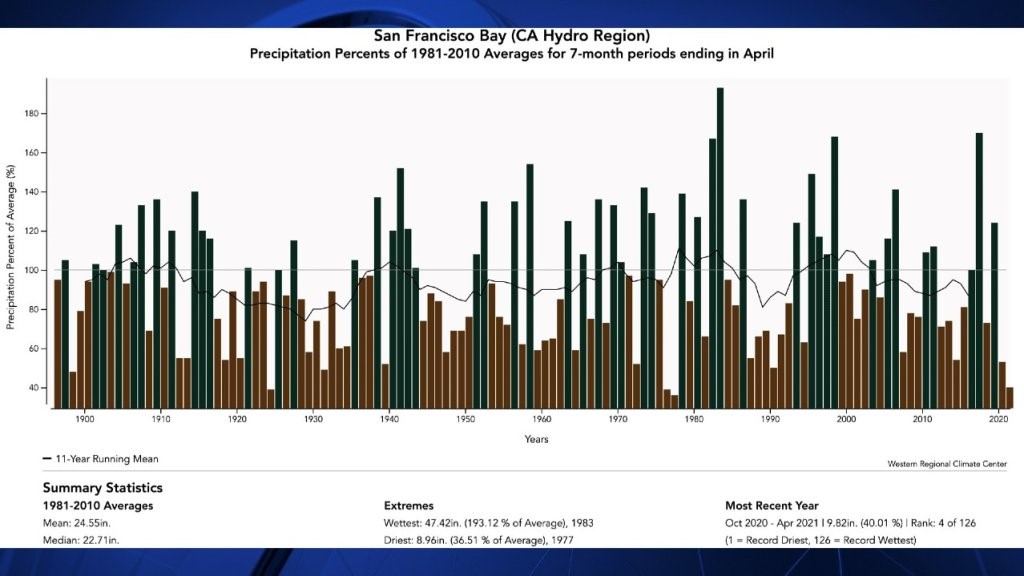

Another drought in California is worsening. After two very dry winters, the reservoirs are shrinking, the risk of fire increases and the water supply seems more vulnerable.

The past two years have been the driest for nearly half a century, from 1976 to 1977. How did the state enter another crisis as the COVID pandemic subsided? Scientists say the state of California can be summed up in two words: “atmospheric flow”.

A growing body of research shows that the state’s water supply is almost entirely dependent on several severe and severe storms each year. And the last two winters are also few.

Also known as the Pineapple Express Storms, which wash away the Pacific Ocean each winter, these moisture-rich atmospheric fluvial phenomena can provide up to 50% of the state’s annual precipitation. When California experiences more atmospheric storms than usual, as in 2017, reservoirs fill up, roads erode and flooding increases. Less common for several years in a row, like this winter and last winter, and California is high and dry.

In other words, the annual water supply forecast for the most populous state is like a gamer putting all of his paychecks on the bike. Are you hitting the correct atmospheric river number? Happy days are ahead. But if you miss the mark, times will be tough.

“Atmospheric rivers literally create or disrupt California’s water supply,” said Marty Ralph, director of the Center for Western Weather and Extreme Weather Events at the University of California at San Diego. “If we don’t have enough, we will face drought. “

Four years ago, in the winter of 2017, California was hit by 51 atmospheric river storms, 14 of which were classified as severe or extreme due to the amount of humidity. It rained so much that year that the state’s historic five-year drought was halted. Flood damage in downtown San Jose was $ 100 million. And the Oroville dam overflow in Butte County, the country’s highest, collapsed in a rainstorm earlier that year, evacuating 188,000 people.

But in the winter of 2019-2020 there were fewer such storms – 43. And the main thing was that only one was strong or extreme. It was the same last winter: 30 riverine atmospheric storms, but only two of them were classified as severe, Ralph said. One of them, Jan. 28, dumped 6 inches of rain on Big Sur after spotting Highway 1. But it was an endangered species.

“Rivers with strong or extreme atmospheres can cause heavy precipitation and snow showers,” Ralph said. “The weak and the moderates can add up. But we are starting to think that the strongest have the greatest impact and are the main drivers of water supply. The effects of vacation or hunger are overwhelming. A 2018 study by Ralph and his colleagues Maryam Lamjiri and Michael Dettinger looked at record rainfall in 20 years.